A third of the way into Sunday’s race at Brno, and there was a group of eleven riders fighting for the lead. That’s the MotoGP race, not the Moto3 race. In the Moto3 race at the same stage, there was still a group of twenty riders at the front.

In Moto2, ten riders were in the group at the front. If you wanted to see close racing, Brno delivered the goods, in all three classes. The MotoGP race saw the eighth closest podium finish of all time, and the closest top ten in history.

Moto2 was decided by seven hundredths of a second. The podium finishers in all three classes were separated by half a second or less. And the combined winning margin, adding up the gap between first and second in MotoGP, Moto2, and Moto3, was 0.360. Are you not entertained?

“A good battle,” is how Cal Crutchlow described Sunday’s MotoGP race at Brno. “I think again, MotoGP has proved to be the best motor sport entertainment there is. Week in, week out we keep on having these battles.”

The race may not have seen the hectic swapping of places which we saw at Assen. The lead may not have changed hands multiple times a lap on multiple laps. Yet the race was as tense and exciting as you could wish, with plenty of passing and the result going down to the wire.

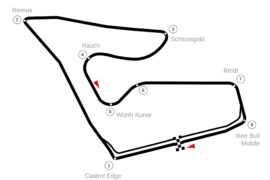

Is it any surprise that Brno should produce such great racing? Sunday’s race reiterated just how crucial circuit layout is in racing. The track is one of the widest on the calendar, with sweeping corners which run into each other.

A defensive line going into a corner leaves you open to attack on corner exit. What’s more, even if you ride defensively, or pass a rider and get passed again, you still end up with the same lap time. Brno, Assen, Mugello, Phillip Island: these tracks are made for motorcycle racing.

Strategy Abounds

There is more to racing than just passing, as the MotoGP race demonstrated. As tense and exciting as the racing was, Sunday’s race was above all one of strategy.

It is an old adage of racing that you really want to win the race at the slowest pace possible: what counts is crossing the line first, now how quickly you get there.

The slower you go, the more tire you have left for that final hectic lap, and the fewer risks you have to take along the way to getting there. But having the chutzpah to actually pull off such a strategy takes courage, intelligence, and experience.

Those qualities were in abundance at the front of the race. Valentino Rossi got the jump on pole sitter Andrea Dovizioso, powering away from the line and into the lead at the first corner.

His lead was only temporary, however: Dovizioso had slotted in behind Rossi and got better drive out of Turn 2, allowing him to slide up the inside and past Rossi into Turn 3. Behind them, Marc Márquez and Jorge Lorenzo duked it out over third place, while Cal Crutchlow sat in fifth.

Andrea Iannone, who got a great start to move up to sixth, soon found himself being swamped by chasing riders. Danilo Petrucci got by in the first half of the lap, followed by Johann Zarco and Suzuki teammate Alex Rins as they made their way up the hill and back to the start.

At the front, Valentino Rossi took back the lead as they rounded Turn 10, holding a tighter line to slide inside Andrea Dovizioso.

But he would not hold the lead to the line: Turn 10 is probably the most important corner on the track, and getting drive out of there can make a huge difference to the amount of speed you can carry as you head up Horsepower Hill.

Dovizioso’s wide line round Turn 10 may have allowed Rossi to slip past inside by holding a tighter line, but it had also given him much better drive out of the bottom corner.

Dovizioso tried to pass Rossi at Turn 11, but could not quite make it through. He tried again into the final chicane, the left-right combination of Turns 13 and 14, and this time he was back into the lead.

Never a Gap

The opening lap set the tone for the race. Dovizioso led, but there was never any room for complacency. Valentino Rossi pricked and poked, and even took over the lead for three laps.

Marc Márquez and Jorge Lorenzo swapped positions, and when Rossi passed Dovizioso, Márquez upped his effort to get ahead of the Ducati rider and latch onto the Movistar Yamaha. Rossi, after all, was second in the championship, and right now, the biggest threat to another Márquez championship.

None of these passes were easy. It took multiple attempts to get past the rider ahead, Brno’s layout betraying the passing rider, leaving him open to counterattack.

By the halfway point, a group of six riders had opened enough of a gap to be sure that they would be battling over victory and the podium places among themselves. Jorge Lorenzo, strong in the early laps, had dropped back a little, while Cal Crutchlow had moved forward.

After losing the lead, Valentino Rossi dropped back steadily. Danilo Petrucci hung on the back of the group, trying to nurse his rear tire. At the front, Andrea Dovizioso led, while Marc Márquez stalked. For both men, their intentions were clear.

Pulling and Pushing

Dovizioso had been trying to balance the lead between not using his tire, and trying to break the group which had formed in the early laps. He varied his pace, faster one lap, slower the next, in an attempt to disrupt the rhythm of those behind.

“I was trying to make something strange, because the group was big at the beginning,” Dovizioso told the press conference afterwards. “It’s always better to have less riders when you start to fight, especially when you have to manage the tire.”

“But it didn’t work because the group stayed six until five laps to the end maybe. But when you are leading, you are able to try some strategy and don’t push too much to make a mistake.”

That upside came with a downside, however. “Unfortunately I couldn’t see the level of the competitors because I was leading,” Dovizioso said. “When you fight, you don’t know the competitors, the strong point and the bad point.”

“So it was very difficult for me to battle with them. I was trying to answer very quick and make my rhythm.”

Not being able to see behind made it difficult to know what he was up against, and especially, what he was up against.

After Rossi dropped away, Dovizioso knew that he still had Márquez behind him, but beyond that, he did not know. After dropping back to fifth, and looking like he was out of podium contention, Jorge Lorenzo found a new lease of life in the second half of the race.

He had passed Valentino Rossi and caught Crutchlow ahead of him, the LCR Honda rider seeing he had a shot at the podium. But Lorenzo was on a charge, and would brook no resistance.

Fuel Aplenty

The factory Ducati rider disposed of Crutchlow at the final chicane, Crutchlow leaving the door open in Turn 14 and Lorenzo leaping at the chance. The LCR Honda rider tried to latch on to Lorenzo’s tail, but he had no rear tire left.

“I’ve complained all year about the front tire, but the front tire today was fantastic. The rear tire gave up the ghost, I had no rear tire left,” Crutchlow said.

Once he lost touch, there was no catching Lorenzo back again. “As soon as you lose that slipstream from the Ducatis, you’re in trouble,” Crutchlow told us.

“Because that’s where they made the race today. They were slower than us in the corners. They can brake well. But they’ve just got an engine that you can’t believe. It’s just a rocket. It seems that Dovi played it perfectly, because he held everybody up all through the race.”

“And then probably changed the maps for the fuel for the end of the race. If they’ve got it, they use the rocket at the end of the race. It seems that’s what Lorenzo did as well, because when he came back past me, he was going way faster than what he was at the start of the race.”

Asked about it in the press conference, Andrea Dovizioso dismissed the idea. “It was just about my riding in the way I used the tire, in the way I pushed,” he explained. “I didn’t change any maps this race. I just ride in a different way when I did a different lap time. “I think nobody had a problem about the fuel.”

The factory Ducati riders probably didn’t need to change to a more powerful engine map. The race this year is 1 lap shorter than in previous seasons, race length cut from 22 to 21 laps, or from 118.866 km to 113.463 to be precise.

Five kilometers less in distance, and some 14 seconds slower in pace, combined with scorching air temperatures would all combine to leave the bikes with plenty of fuel to burn. Dovizioso and Lorenzo went faster because they could, but probably because they had speed in hand.

Next Victim

Once he had dropped Crutchlow, Lorenzo set his sights on Marc Márquez. He launched an attack on the Repsol Honda rider at Turn 13 at the end lap 18, then found himself carrying enough speed to swoop inside Andrea Dovizioso in the final corner.

But that left him running wide on exit, and Dovizioso came straight back to take the lead.

The game was afoot. There was no love lost between the Ducati teammates, after Lorenzo and Dovizioso had exchanged verbal shots in the media, though to be fair, Lorenzo had fired first. Lorenzo attacked, and Dovizioso parried, Márquez waiting patiently for a mistake.

The Ducati pair swapped the lead once on the first half of the penultimate lap, Lorenzo taking a second shot as they got halfway up Horsepower Hill. Márquez saw an opportunity in the final corner, but Lorenzo held his line and forced Márquez to back off.

It would all come down to the final lap. Márquez saw a gap at Turn 3, and squeezed himself inside Lorenzo, victory clearly on his mind. Lorenzo tried to hold the outside line to give himself the advantage into Turn 4, but Márquez was a fraction too far ahead.

But Lorenzo was not ready to give up: the Spaniard dived hard up the inside of Márquez into Turn 5, forcing the Repsol Honda wide, a move more reminiscent of Lorenzo’s time in 250s than the impeccably clean rider he had become in MotoGP.

Reminiscent, perhaps, of Marc Márquez, a stuff up the inside giving Márquez no option but to back off.

To the Line

The battle gave Dovizioso the narrowest of breathing space, but the Italian tried to exploit that, push hard to try to create a break. But Lorenzo was not done: with Márquez behind him, he was off to hunt down Dovizioso, hounding him up the hill once again in search of victory.

He looked like catching his teammate at Turn 11, but the gap was just too much to attempt a pass. Dovizioso, Lorenzo, and Márquez crossed the line in the order in which they had exited the bottom of the hill.

It cannot be said that they had not given it their all. Andrea Dovizioso set the fastest lap of the race as he crossed the line, though that honor would stand for less than two tenths of a second.

Jorge Lorenzo would take the fastest race lap as he crossed the line in second, and Marc Márquez set his personal fastest lap on the final lap as well, quicker than Dovizioso but slower than Lorenzo.

The leaders were a full second faster than Rossi and Crutchlow behind them, opening the gap to nearly three seconds to fourth.

On the previous lap, it had been Cal Crutchlow in fourth, but a mistake in Turn 3 gave Valentino Rossi a sniff of fourth, and two more valuable points in the championship.

Rossi sat on the back of Crutchlow, and grabbed fourth place in the final corner. Crutchlow acknowledged that he had been beaten fair and square.

“He made a lunge, perfect, exactly what I had been doing to everyone else in the race, and he did it to me in the last corner, so I suppose I got my comeuppance,” Crutchlow told us after the race. “I tried to square it off.”

“I hadn’t been on the inside kerb the whole race, because we don’t really use it. And then I looked at it and thought, I’ve got to go onto it, but it was full of mud from the tractors, and I couldn’t move on it. It just spun and didn’t go anywhere, or else I would have drove him to the line.”

Still Got It

Andrea Dovizioso was elated with victory. It was his first win since Qatar, and a good omen ahead of a string of tracks he feels strong at. It helped right the ship a little, his championship having run aground with three DNFs at Jerez, Le Mans, and Barcelona, and confirmed to Dovizioso that was still competitive.

If anything, even more competitive than last year. “When you win six races like last year, everybody expects you have to win,” the Italian told the press conference.

“So we won just one race in Qatar and everybody says, you are living a bad moment. But if you really study everything, it wasn’t like this because we are faster than last year in every track. I think we did a small step during the winter.”

The three crashes at Jerez, Le Mans, and Barcelona had disguised how strong the Ducati, and Dovizioso himself, really are, he said.

“We did three mistakes, so if you look at the championship and if you look at the last two results before this you can think that, but if you study in the details, if you look last year and you make a comparison, it’s not like this. This weekend is a confirmation. Our bike is a bit better than last year.”

There is still work to do, however. “I’m not happy 100% in the way we manage the tire. I don’t know if it’s our bike or is the tire. We are working on that. This weekend we improve a little bit to manage that, but still I’m not happy.”

“I’m not happy about that details. Our bike in this track, it was a bit better because we have a strong acceleration. That give us the possibility to save the tire and be fast. But still I’m not happy 100%.”

What was important was the way in which Dovizioso had won the race. He was still smiling about the victory the day after. “It was a really important race, in the way we did it,” he said. “I was fighting with three riders, and at the end we won. And we are speaking about Valentino, Marc, and Jorge. And this is good.”

He had controlled the race from the front, tried to break the group up to a more manageable size, then pushed hard at the end to secure a win.

Ducati’s first win at Brno in eleven years, since Casey Stoner beat John Hopkins and Nicky Hayden in the Australian’s first year on the Desmosedici GP7. This was the Dovizioso of old.

One-Two

Even better for Ducati was Jorge Lorenzo’s second place, securing Ducati’s first ever one-two, and even their first double podium at Brno.

It was a mark of both how much better the Ducati has become in recent years, as well as how much Lorenzo has adapted his riding style to the Ducati, at last. Lorenzo was fierce and aggressive, a throwback to the rider he used to be back in 250s, though his passes were hard but clean.

The way he dived up the inside of Márquez, leaving the Honda nowhere to go without actually causing contact, was tough as you like. It is a sign of the confidence he feels with the Ducati, something that had been sorely missing last year.

He has been forced to change his strategy because he did not believe the front tire would last. His previous wins on the Ducati – and most of his wins on the Yamaha – had come when he had taken off from the start and led almost every lap.

“I was almost obliged to change my strategy, because especially we have some problems to finish the race on the front tire on the right side,” Lorenzo said.

“So I needed to ride quite a bit different from the beginning. Taking profit of a not so good start, I decided to stay in third, fourth position for so long to save energy, to save tires. This was new for me, very new.”

It proved to be the right choice, however. “This time, based off this new strategy because I have a very good speed and I was very competitive, especially on braking compared to Marc and Dovi.”

“Unfortunately I lose just slightly a little bit in the acceleration. So that made me brake a little bit farther than them. So I was catching them but maybe too far. So this made me take some risks in some chicanes to try to overtake Andrea, which normally I will try in the normal braking. So it was a great battle for the three.”

If the race had been one lap longer, he said, he might have won it.

Playing the waiting game had been risky, but paid off in the end. “At the beginning I was very calm, so I was feeling well,” Lorenzo said. “Probably in the middle of the race I was keeping more or less the same strategy but I was losing a little bit too much in some part of the track.”

“I lose half a second, seven tenths. Luckily for me I saved the tires very well, and in the last seven laps I felt really well. I was recovering so much in mostly of all the braking zones. So this gave me the possibility and the energy enough to be very aggressive and attacking in the last three or four laps.”

The return of strategy is a result of the switch from Bridgestones to Michelins. When Bridgestone were spec tire supplier, the only question was which front tire the riders would use. The front would provide endless confidence, the rear had little grip and a near infinite lifespan.

Now, the bikes can use all of the tire available, and that favors the intelligent, as much as the brave.

“Some years ago with different manufacturer of tire you could be full power from the first corner to the last one normally and be very consistent and don’t worry about the rear tire,” Lorenzo explained.

“Now you have to worry a lot. You have to plan a lot the strategy and this makes our race always a little bit of tension in that area.”

Left Wanting More

It was a visibly frustrated Marc Márquez who turned up to the press conference. Márquez had made a conscious decision to play it safe and take the points, as he was ahead of Valentino Rossi, second in the championship, and could afford to concede a few points to Dovizioso and Lorenzo, as his lead over them is more than comfortable.

But such decisions never sit well with Márquez, whose instincts are always to try to win, if he is in a position to take a shot. He could have done so at Brno, but it would have needed him to risk too much.

Márquez was happy that the race had been run at such a slow pace, he said, as it meant less risk to stay at the front.

“The race was slow, but for me it was welcome. If you’re slow, there’s less risk. More chance to finish the race in a good way. For me, I saw that the pace was slow but I said, okay, I will be behind them.”

“To be in front was just take a lot more risk, and without the slipstream I was able to be a little bit faster but with a lot of more risk.”

“I saw the pace was slow but for me was not a problem because my target is finish all the races. Worst result of the year on the finished races, but this is positive,” Márquez explained.

The Repsol Honda rider has two no-scores, after a crash at Mugello and his wild and reckless chase at Argentina. But when he has finished, he has finished either first or second. Brno was the first time he finished worse than second.

That is not a bad record at all, and a sign of just how consistent Márquez has managed to be.

The Need for Speed

In the end, he had been beaten by the speed of the Ducatis, Márquez said. “The speed was good,” he said. “I was able to ride well, save the tires, but the problem arrive when you need to fight against Ducati riders because they have a really strong acceleration.”

“More than acceleration, the top speed. Then are really strong brake points. Then was so difficult to overtake them. But I said, okay, I will try but don’t be crazy.”

“The good thing is that Valentino was already behind so my main target was try to increase the advantage in the championship, which we did. We know that Andrea gained some points, also Jorge, but they are still 68 points behind me. So we are on the way.”

At Brno, Marc Márquez showed he still had his eyes firmly fixed on the prize, that prize being the long-term goal of winning a championship, rather than the short-term goal of winning a race.

That long-term goal doesn’t always sit well with him, that much is clear, but his focus remains the same. And the strategy is paying off: Andrea Dovizioso may have closed the gap by 9 points to Márquez, but he is still 68 points behind with nine races left to go.

Márquez only needs five second places and five third places in the remaining ten races to retain his title. Dovizioso needs to win everything, and still needs help from other riders getting in between himself and Márquez at six races.

Brno was also the place where Valentino Rossi saw the championship slip out of his own control. Márquez only gained 3 points on him, but that was enough to widen the gap from 46 to 49 points. Winning the remaining races is not enough, he will need help from other riders to get between Márquez and himself.

Down, But Not Out

Winning the remaining races is very unlikely, for anyone, but especially difficult for Valentino Rossi and his Movistar Yamaha teammate Maverick Viñales.

Brno was the 20th successive race in which Yamaha has gone without victory, closing in worryingly on the previous longest winless streak of 22 races in 1997 and 1998. The difficulty remains the same as ever: tire wear, and problems of acceleration.

“You know, I think my race was very good,” Rossi said. “Also the start and on the first lap I was competitive and I stayed in front. But unfortunately, when the rear tire lost a little bit of grip and start to slide, for us the acceleration is difficult, we started to lose there.”

“Unfortunately I wasn’t strong enough for the podium. After the practice we know this. We know that Marquez and the two Ducatis were stronger than me. I tried. I used the hard rear that is the right choice.”

“I did a very good battle with Crutchlow. At the end I was able to overtake him. But unfortunately I was not enough for the podium.”

The good thing about the race was that he had spent a lot of time behind the Ducatis and the Hondas, and been able to study their strengths and weaknesses, Rossi said.

“From this point of view, today was an important race,” he said, “because I followed Dovi, I followed Marquez, I followed Lorenzo, I followed Crutchlow. But it’s everything that I already know.”

“When they open the throttle they are able to accelerate in a better way, they are able to use the tire in a better way and this is where we suffer. Our bike, in terms of balance and mechanically, is very good.”

“In fact, in the qualifying we are always competitive. But in the second half of the race unfortunately we have to improve.”

A Corner Turned?

Things are not looking rosy for Yamaha. Austria is up next, a track which is truly awful for the Japanese manufacturer. Silverstone and Misano may be better, but if, as suspected, the problem for Yamaha is mechanical, crankshaft mass, then they may have to weight until 2019 for a fix.

Electronics can only go so far in mitigating an overly eager engine, and so they face a long road ahead of them.

There is a bright side to Yamaha’s current predicament, of course. The fact that the M1 is so competitive despite such a clear engine defect means that the rest of the package is outstanding.

And Rossi and Viñales can spend the rest of the year perfecting their chassis setup, and making the bike better. When a new engine does arrive – perhaps as early as the Jerez test at the end of 2018 – and if it fixes their current problems, they could find themselves in excellent shape.

Optimists have reason to believe that 2019 could be the year of the Yamaha. Valentino Rossi is riding as well as he has ever been, and shows no signs of slowing down. Maverick Viñales will have a new crew chief, and with it, new hope.

If the engine is good enough to make the tires easier to manage at the end of the race, and the new spec IMU removes the advantages that other factories (we suspect Honda and Ducati, but have absolutely zero proof of that) currently have, then Marc Márquez, Andrea Dovizioso, and Jorge Lorenzo will have a real fight on their hands.

Down and Out

2019 may be looking rosy, but Brno was particularly bleak for Maverick Viñales. First there was the public spat with crew chief Ramon Forcada, after Yamaha told Forcada Viñales didn’t want to work with him, while Viñales hadn’t said a word to Forcada.

Then there was the stern talking to which Viñales received ahead of his media debrief on Saturday. And is if to insult to injury – or injury to insult, given the circumstances – Viñales was taken out at Turn 3 through no fault of his own.

Stefan Bradl missed his braking point, hitting Bradley Smith, who in turn took out Viñales.

Bradl claimed he didn’t understand what had happened, but Jack Miller had seen the whole thing unfold before his eyes, and his front wheel.

“It was right in front of me,” the Pramac Ducati rider said. “I had to slow down because of it. Bradl just tried to pass us all in one go, locked the front and it was dominoes from there. He hit Smith, Smith went down and their two bikes cleaned up Maverick, who went over the highside.”

“It was a nasty little crash. I had to grab the brakes and almost stop just to wait for the bikes to slide past my front tire. I thought, ‘here we go, it’s déjà vu all over again’. I was fortunate enough not to get too tangled up in it this week.”

“But I mean here’s always a hard one, especially after all the Dunlop rubber is one the ground and we go out there, trying to make up a couple of positions and it is slippery.”

Viñales hadn’t known what hit him, quite literally. “I honestly don’t know what happened,” he said. “But anyway I just saw I think one bike coming across, hit my wheel and I just fly. I honestly didn’t expect in the third corner but anyway it’s like that.”

“This is the consequence of starting twelfth. You can be involved in those crashes.”

Starting twelfth was down to the mistake his team had made on Saturday morning, by not sending him out for two runs on new soft tires. But they had spent too long looking for a decent setup, Viñales said.

“To find the setup in the warm up is too late. We should find out Friday afternoon I think. But we need to keep working and for sure give more attention to FP3 to go into Qualifying 2 directly, because for sure I could make better lap times.”

The tension over the weekend hadn’t affected him, Viñales claimed. “Honestly when I put the helmet on I forget everything and I try to make my best always and I work really hard every day trying to be in the front,” he said.

“So I think what we should do is really pay attention to the changes on the bike and which setup we want to use because it’s really important. I ride different to the other Yamaha riders I think, I’m a little bit more aggressive, so I need different things.”

Orange, Crushed

If Viñales had had a bad weekend, it wasn’t nearly as difficult as KTM’s. After losing test rider Mika Kallio to injury – due to make a wildcard appearance here and next week at their home Grand Prix in Austria – Bradley Smith was able to use the new engine with the counter-rotating crankshaft.

He only used it in practice, however: the bike suffered four different problems during practice, causing Smith to switch back to the old engine for the race, for the sake of safety.

As it happened, he needn’t have bothered, as he was wiped out in the first corner by Stefan Bradl. And that was after Pol Espargaro had suffered massive crash and broken his collarbone during warm up.

“Today was a disaster,” KTM team boss Mike Leitner said afterward. “I think it was the worst day since we started this project. We were in a bad situation in the morning with the crash of Pol. The only positive point was that Bradley was not hurt. He’s OK. We have to take it as it is.”

Espargaro’s injury leaves KTM no time to find a replacement for their home race next weekend, and down to one rider for Monday’s test. The KTM RC16 MotoGP project has had plenty of ups and downs through the two short years of its life, but Brno was the absolute low point.

Luckily, they – or rather Bradley Smith – have a chance to redeem themselves in just a few days. The paddock is already on its way to Austria.

Photo: © 2018 Tony Goldsmith / www.tonygoldsmith.net – All Rights Reserved

This article was originally published on MotoMatters, and is republished here on Asphalt & Rubber with permission by the author.